The How

About the Lesson

Purpose

Introduce the methods, audiences, and best practices of communicating mathematical content to technical audiences

Goals and Outcomes:

- Participants will be able to describe the ways storytelling can help with technical communication

- Participants will be able to assess stories for different narrative structures

- Participants will be able to critically analyze a communication for the necessary components for it to be a story

- Participants will tell their own story multiple ways

- Participants will be able to determine the characters and events in their stories

Lesson Notes

Listening and Telling Activity (Half-Life)

- Split into Pairs

- Share your research draft in 2 minutes or less

- Your partner will tell it back to you in 1 minute or less

- Repeat by telling your story and listening to it back again in 1 minute and 30 seconds respectively

- This exercise helps people focus their stories and figure out what the main points are, both by forcing them to continue to make it shorter and shorter and shorter and by showing them exactly which parts other people are taking away and finding most memorable.

The Big Questions

for all Communications

- What is your Point?

- What is your Goal?

- What does success look like?

- Who are your audience?

- Always keep these in mind!

Communication Styles

-

Explainer

- Area focused

- Problem Focused

- Application Focused

-

Marketing

- Fund Raising

- Policy Push

- Result Publicity

-

Narrative

- Person focused

- Subject focused

- Fiction

Why Stories?

- Humans love stories

- Oldest Human Art

- What are some of your favorite stories

- What makes them special?

- Information divorced from a setting or narrative is hard for people to internalize

- Do you recognize these of equations?

- How about now?

- Do you recognize these of equations?

- Stories transport readers into the content (Green & Brock, 2000)

- Stories are one of the basic blocks of memory, and perhaps the most fundamental (Schank & Abelson, 1995)

- People engage more if there is a narrative flow instead of just a list of information

- Narratives can lead to better educational outcomes - especially if personalized or dramatized (Glaser et al., 2009)

- Faster to read (Zabrucky & Moore, 1999)

- Stories can increase trust (Fiske & Dupree)

- Stories can increase the sense of STEM belonging and identity

Not all Roses

- There is a history of erasure of the people with the least power and privilege, as well as their contributions to the world, from stories (Djanegara)

- Used the wrong way stories can to feelings of tokenization and lack of belonging (Dawson)

- Stories can be used to drive misinformation and lies (Dahlstrom)

- Stories/extreme examples can overpower the actual results for readers (Gibson & Zillman, 1994)

What is a story

- Is it:

- Beginning

- Middle

- End

- Maybe:

- Beginning

- Middle

- A Twist (Washington)

- End

- Could it be:

- Change (Dicks)

- Or even:

- Characters

- Events

- Change

Was it a Story Activity

- Think back to what you told your partner during the half life activity

- Was it a story?

- How could you make it a story?

- Outline your draft as a story, including your change

- This exercise helps people analyze a communications and look for the tell tale signs of it being a story and develop the skills for creating stories.

Dramatis Mathematicae

- Characters do not have to be people

- A problem

- A subject

- An object

- An email

- Anything that something can happen to and that can cause something to happen can be characters

Moving Things Along

- Events are the things that happen

- These can be internal to characters

- The most important events are the ones that drive or cause the change

Mathematical Deltas

- A story’s change can be anything

- A person realizing mathematics IS for them

- A theorem going from conjectured to proven

- How a subject grew over time

- The beginning of a collaboration

- It just means that the characters can not be exactly the same at the end of the story as they were in the beginning

The Story Sentence

- Subject - Characters

- Verb - Events

- Complement - Change

Your characters went through an event and were changed in some way.

Story Sentence Activity

- Identify the characters and events in your story

- Determine if they are integral or incidental, I.E. are they absolutely necessary to tell and understand your story?

- A good way to help with this is to determine if they have to do with your story’s change or your point

- Write a story sentence with your integral characters, events, and change

- Share your sentence with your partner

- This exercise helps with the very hard practice of editing by making it clear how few parts of a story are really required to tell it. This does not mean that only integral characters and events should be included in a story, but the fewer non-integral parts there the better in most cases.

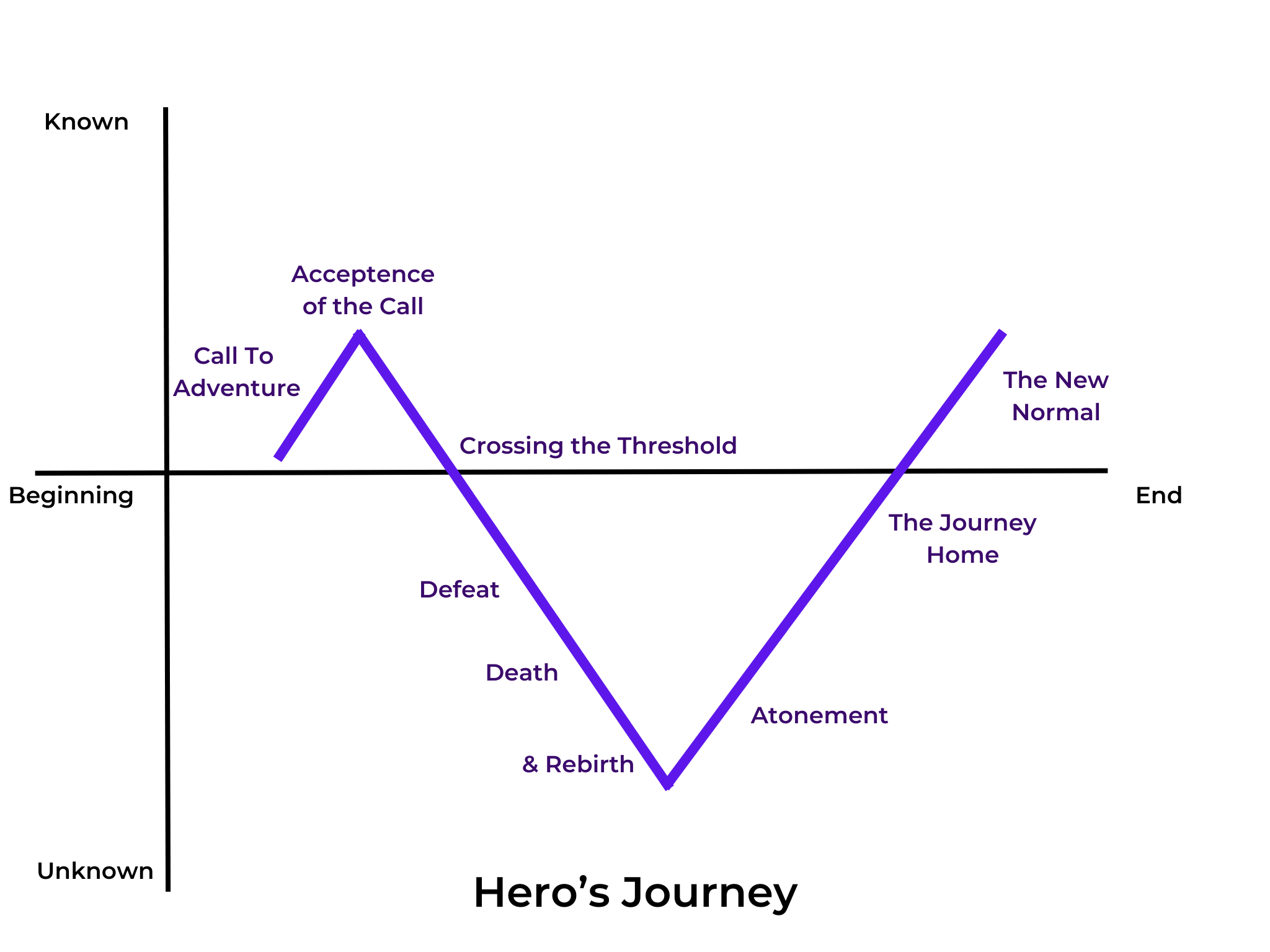

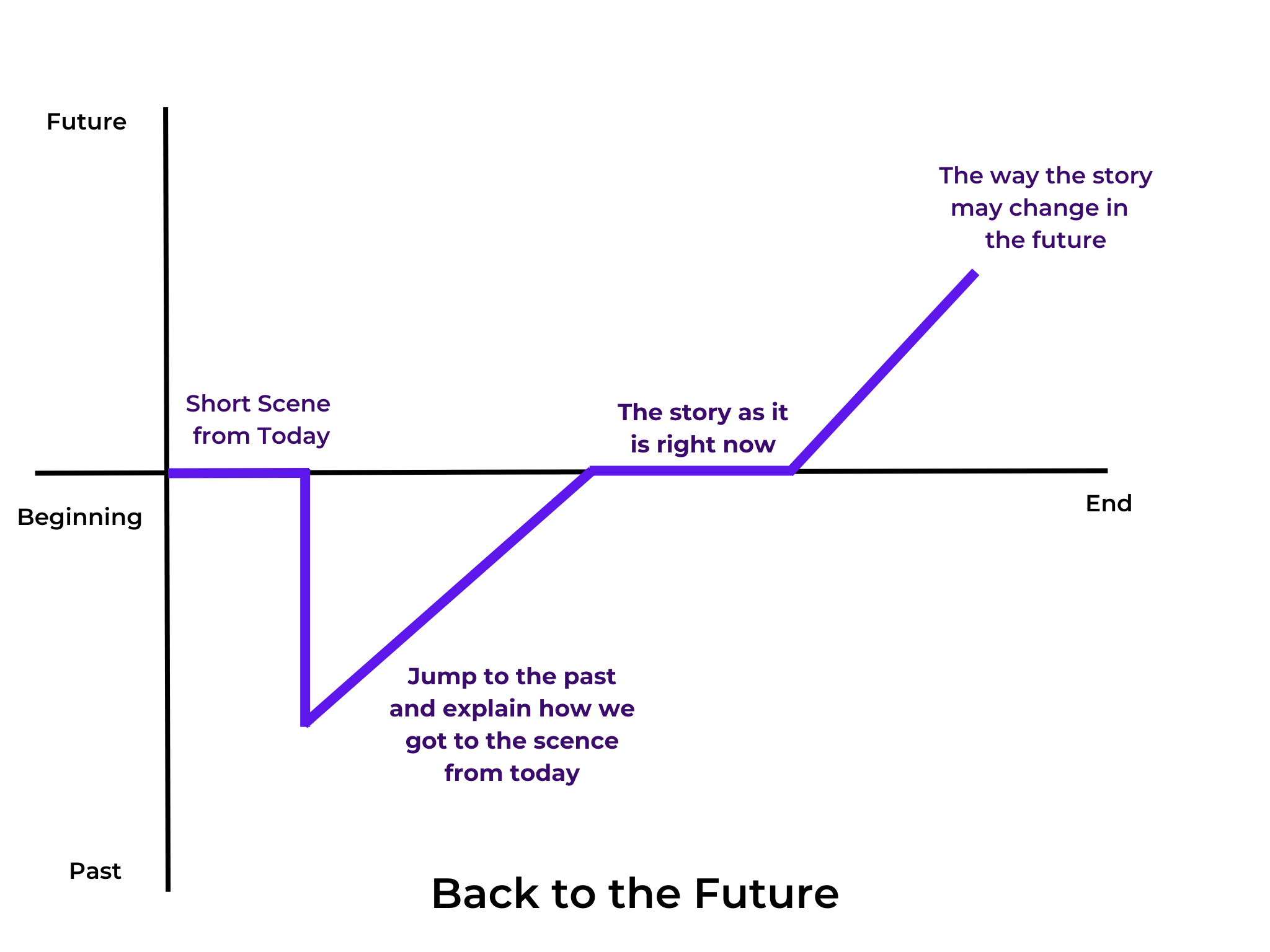

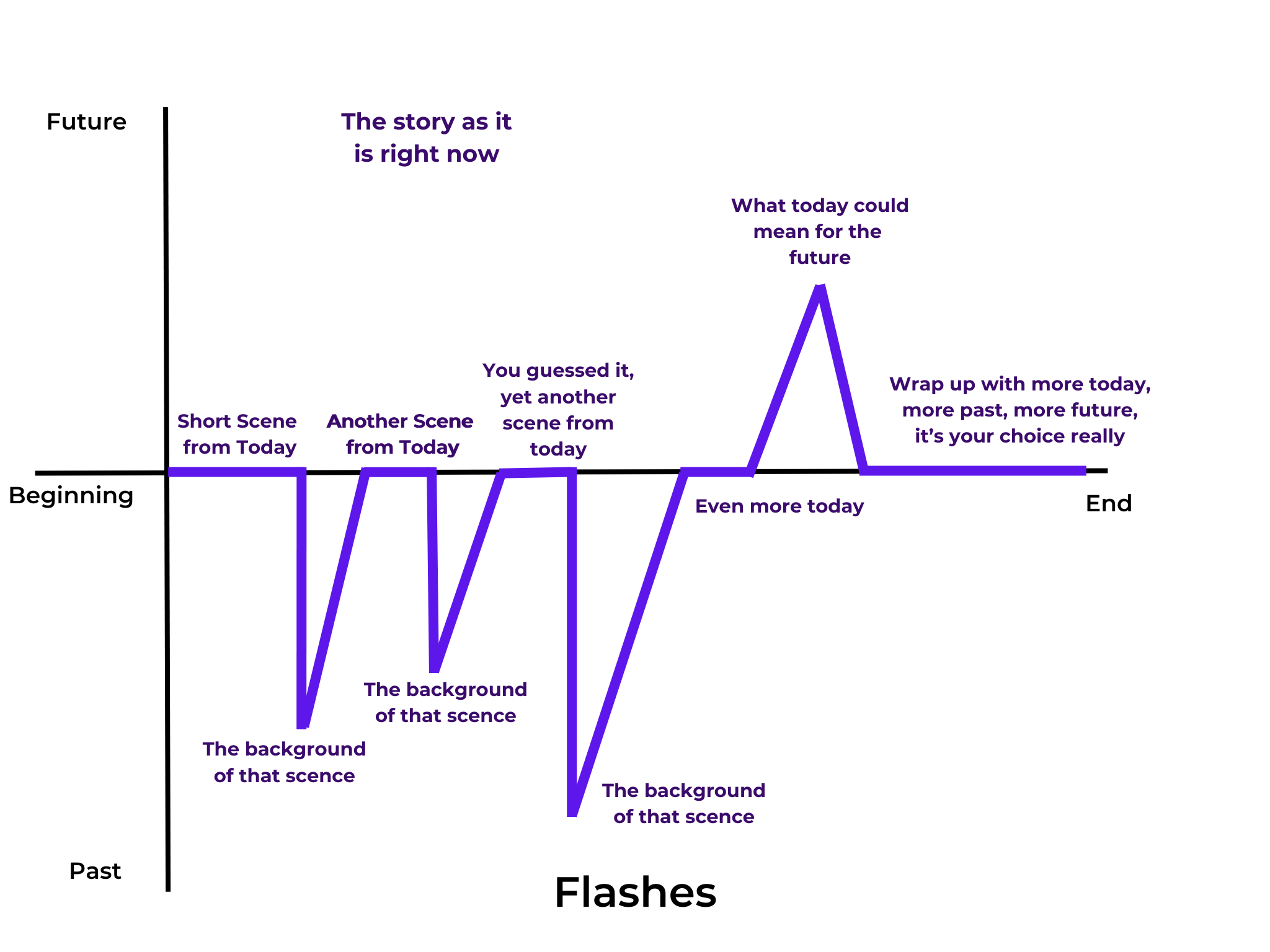

Narrative Structures

- Story Structures are not mutually exclusive

- Pay Attention to the axis labels

- If the axis labels are not the same then the story structures can both be true at the same time

- e.g. Calm-Active, Ill Fortune-Good Fortune, Past-Future

- Lots of different ways to think of them. By how much is happening, by the timeline of the story, by the emotional arcs, by the depth of focus. We will see examples of all of these and more

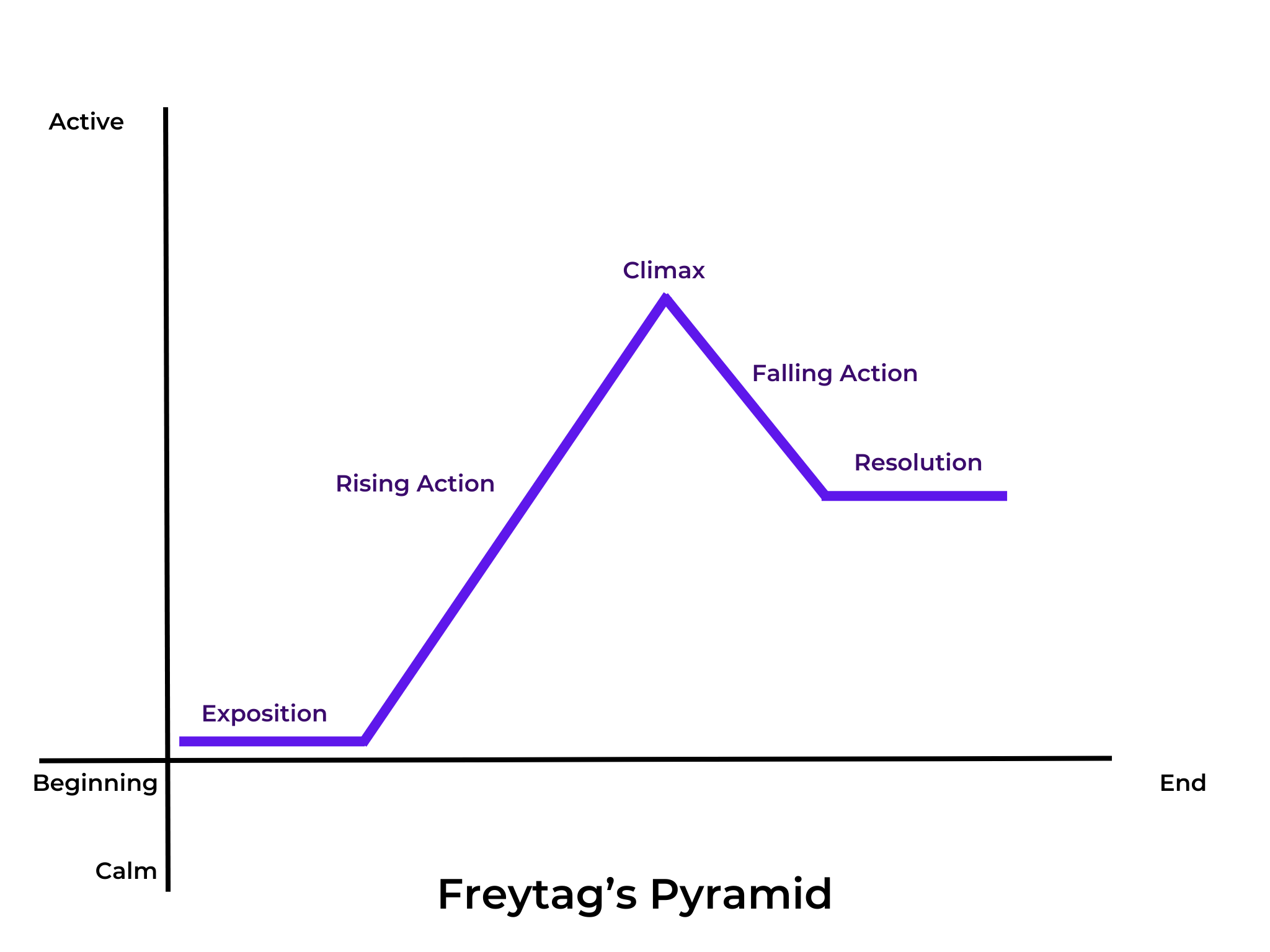

- Freytag

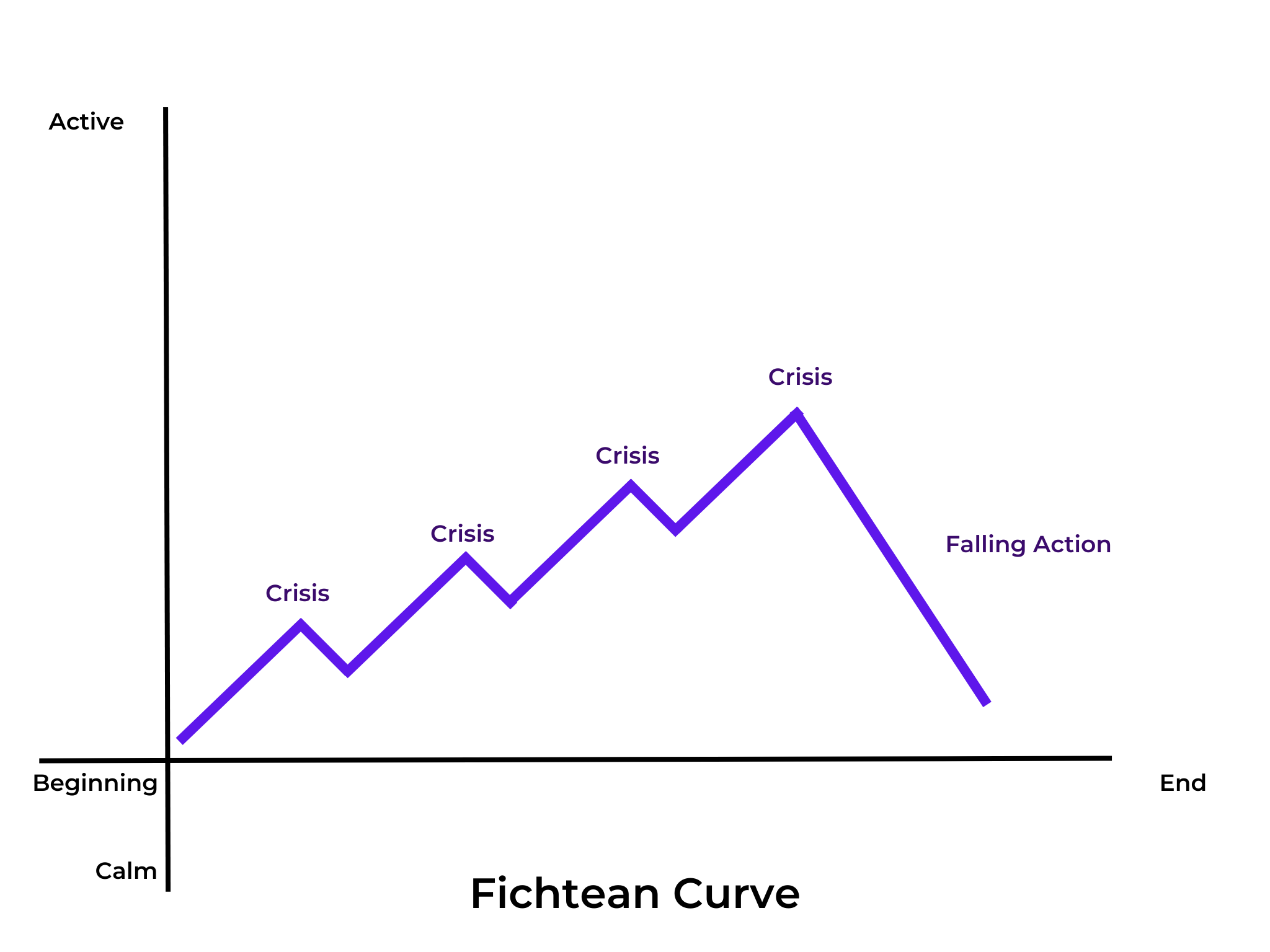

- Fichtean

- Hero’s Journey

-

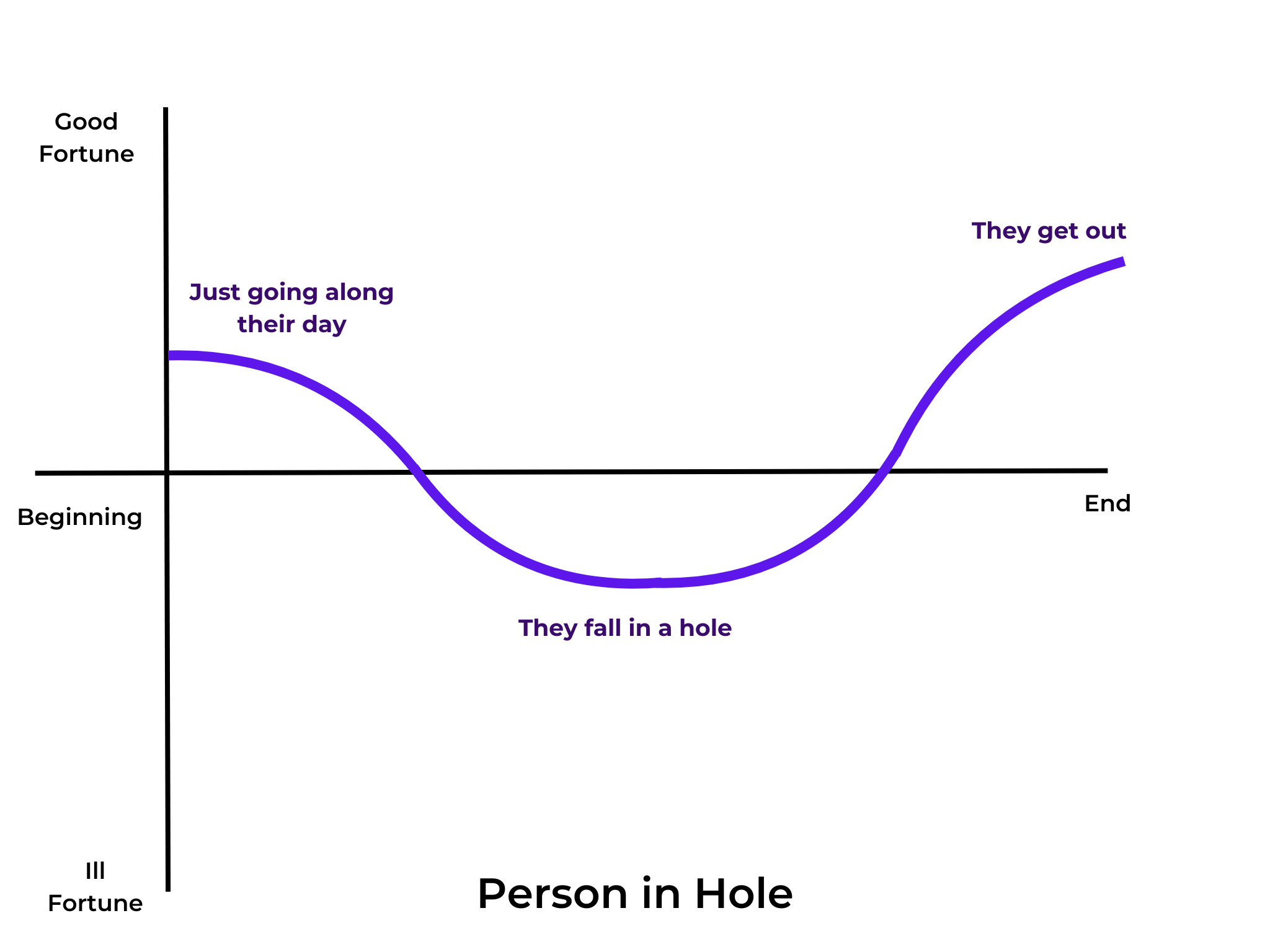

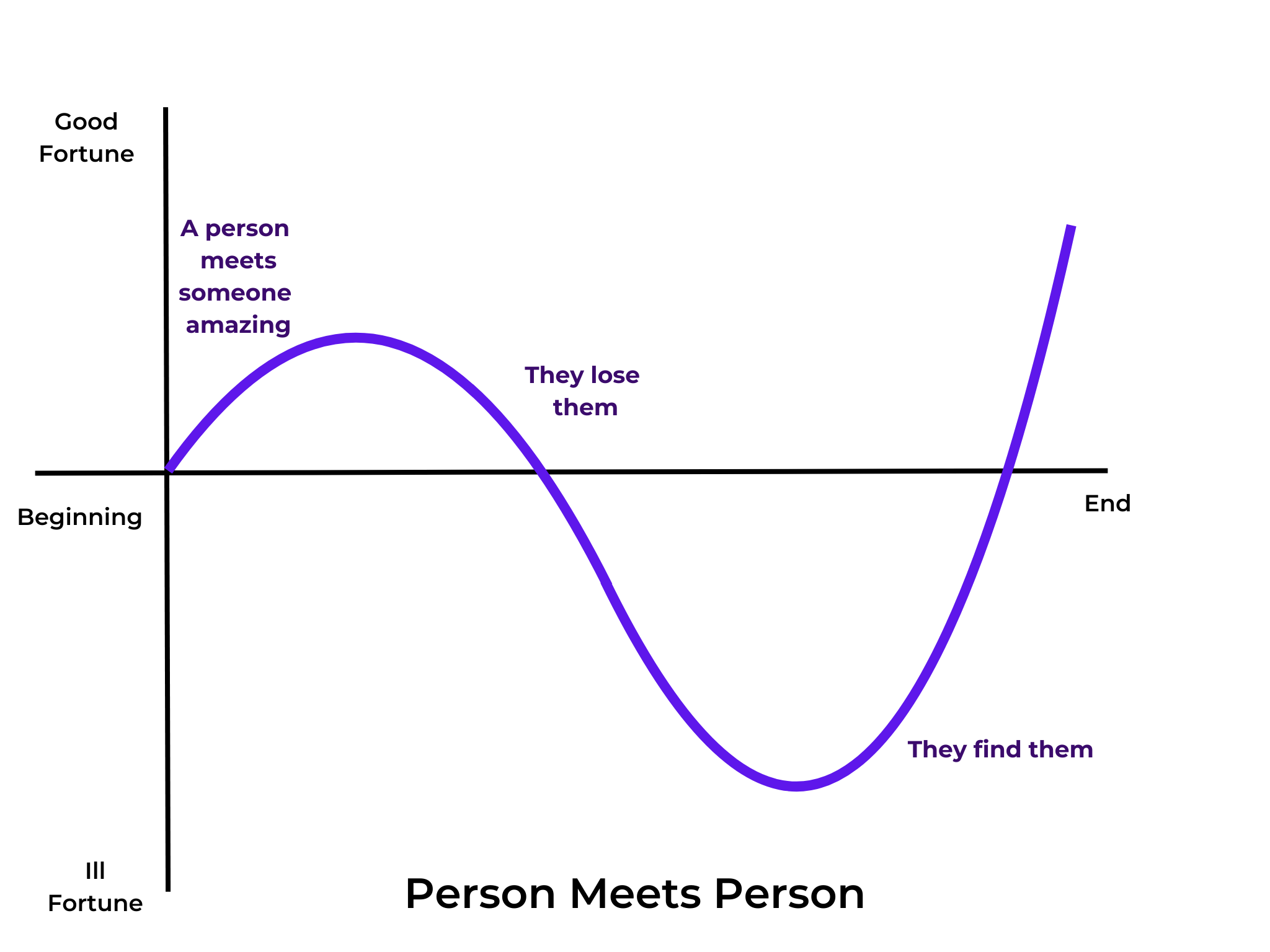

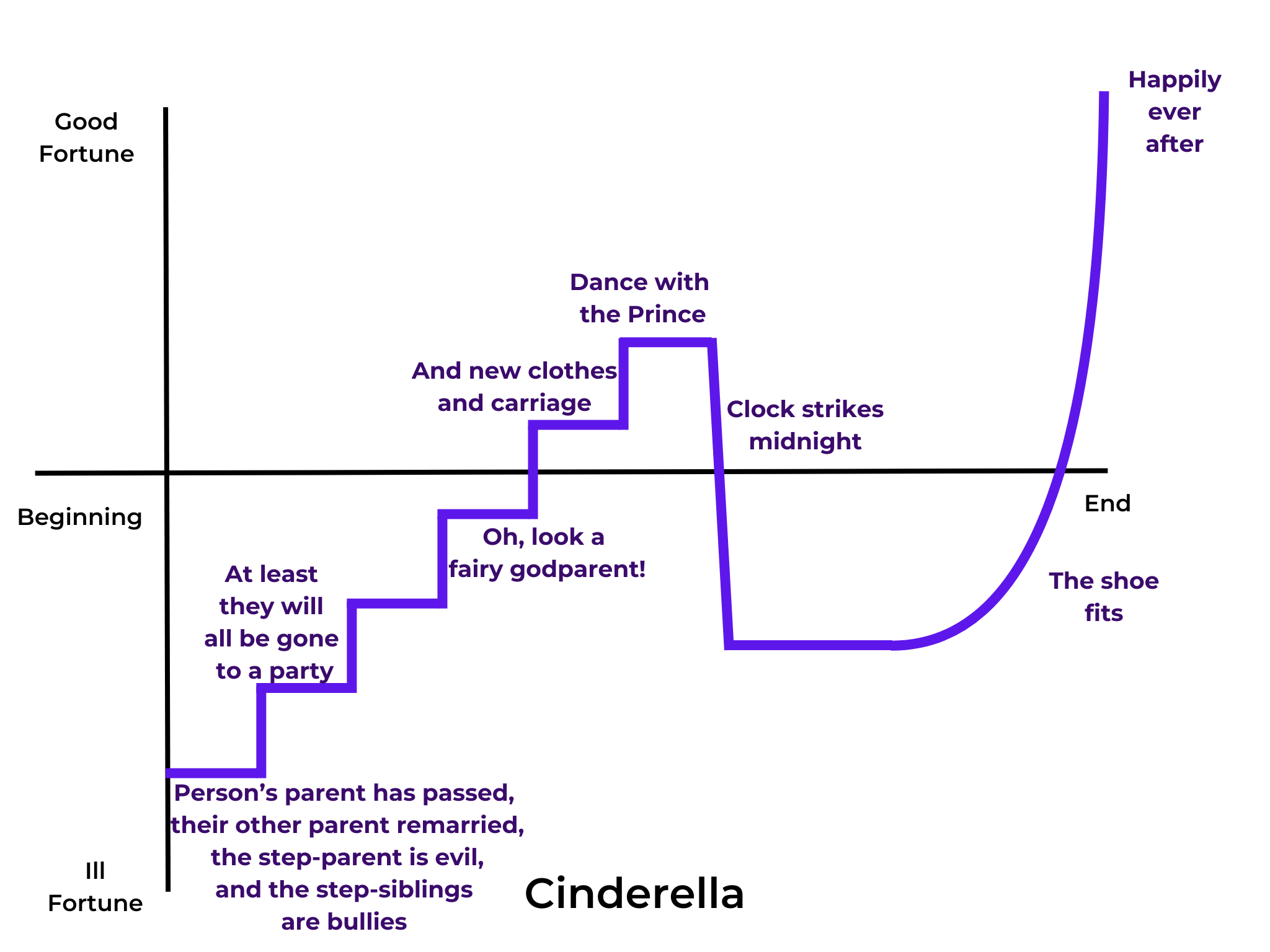

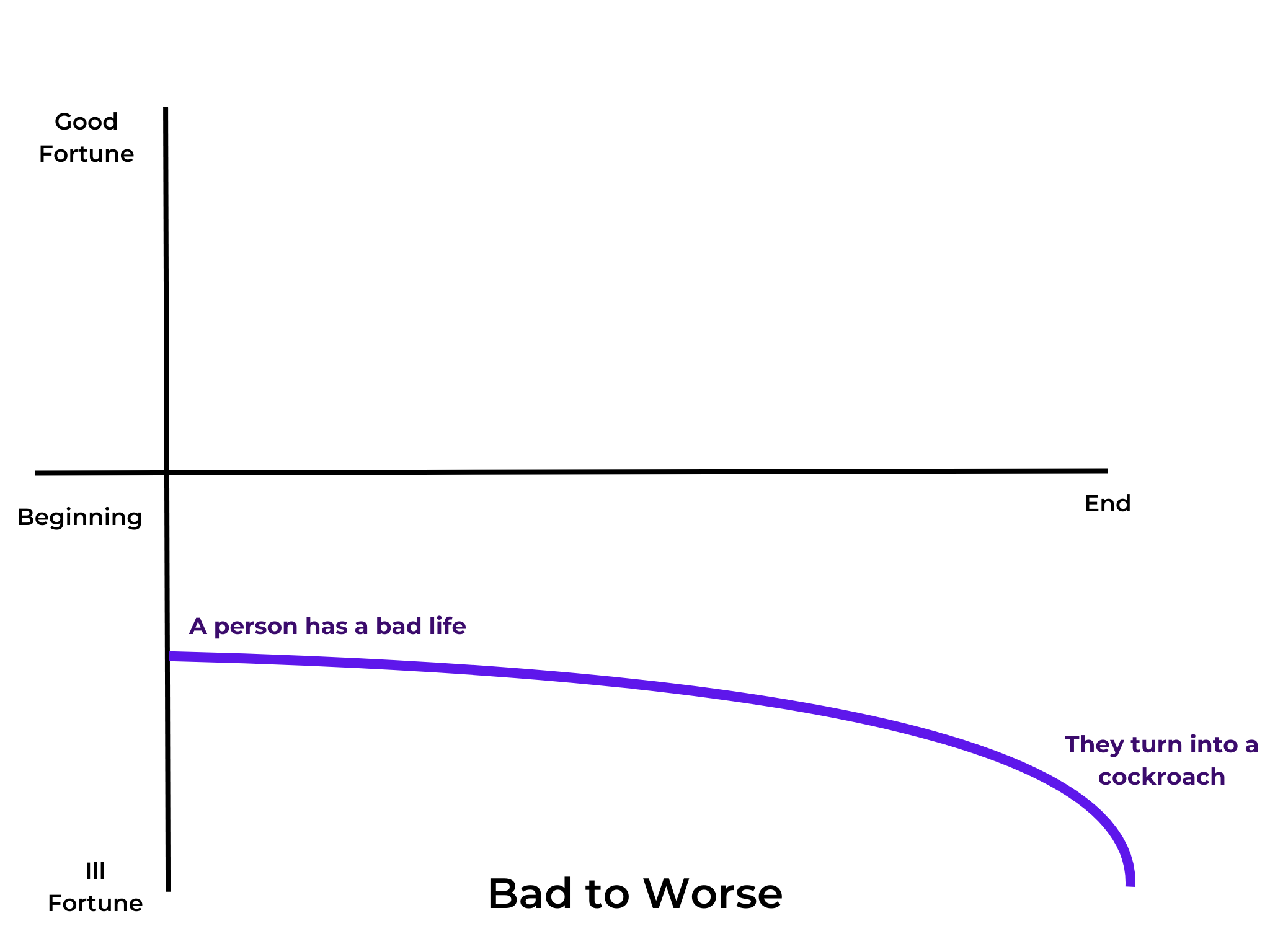

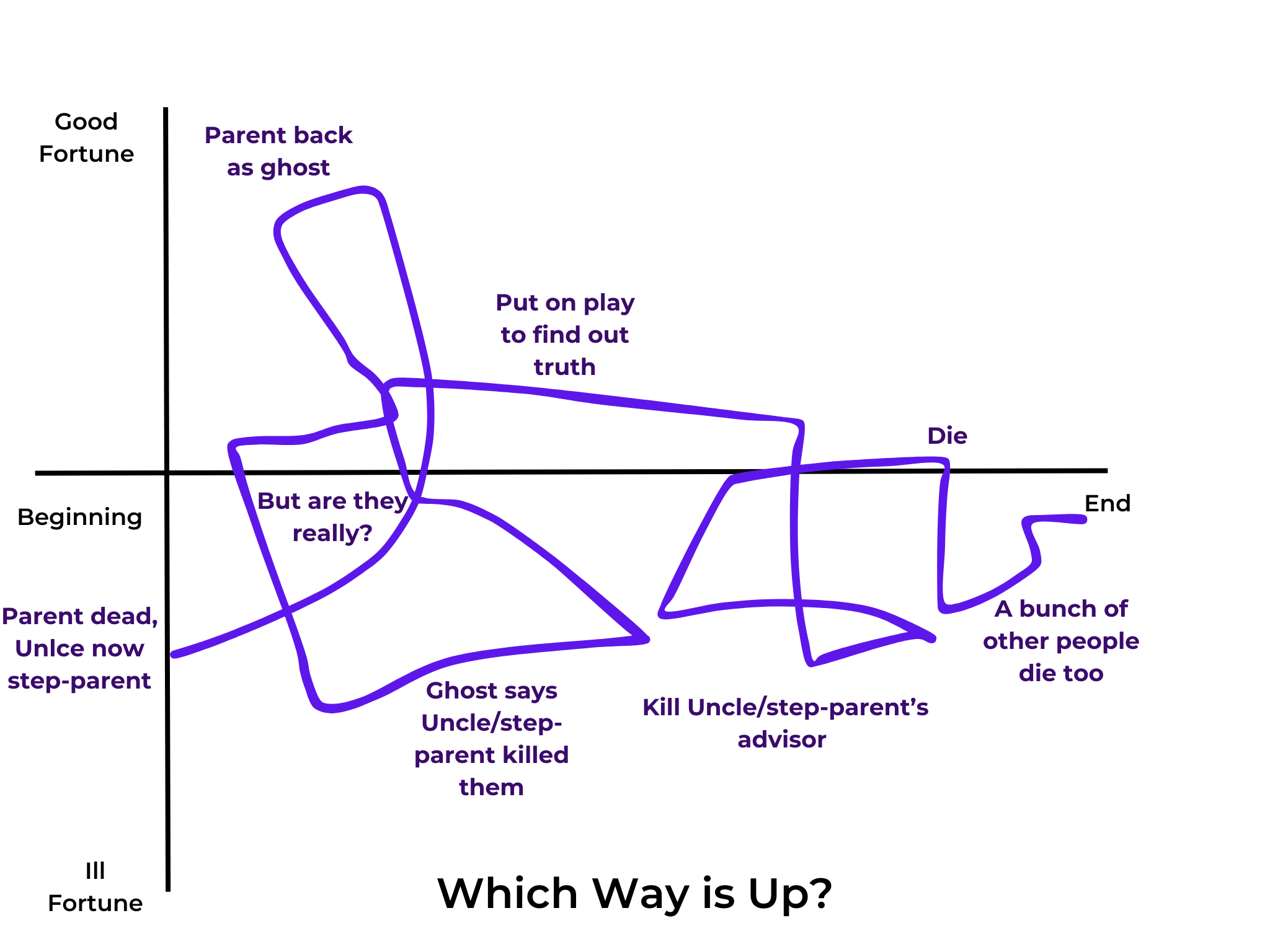

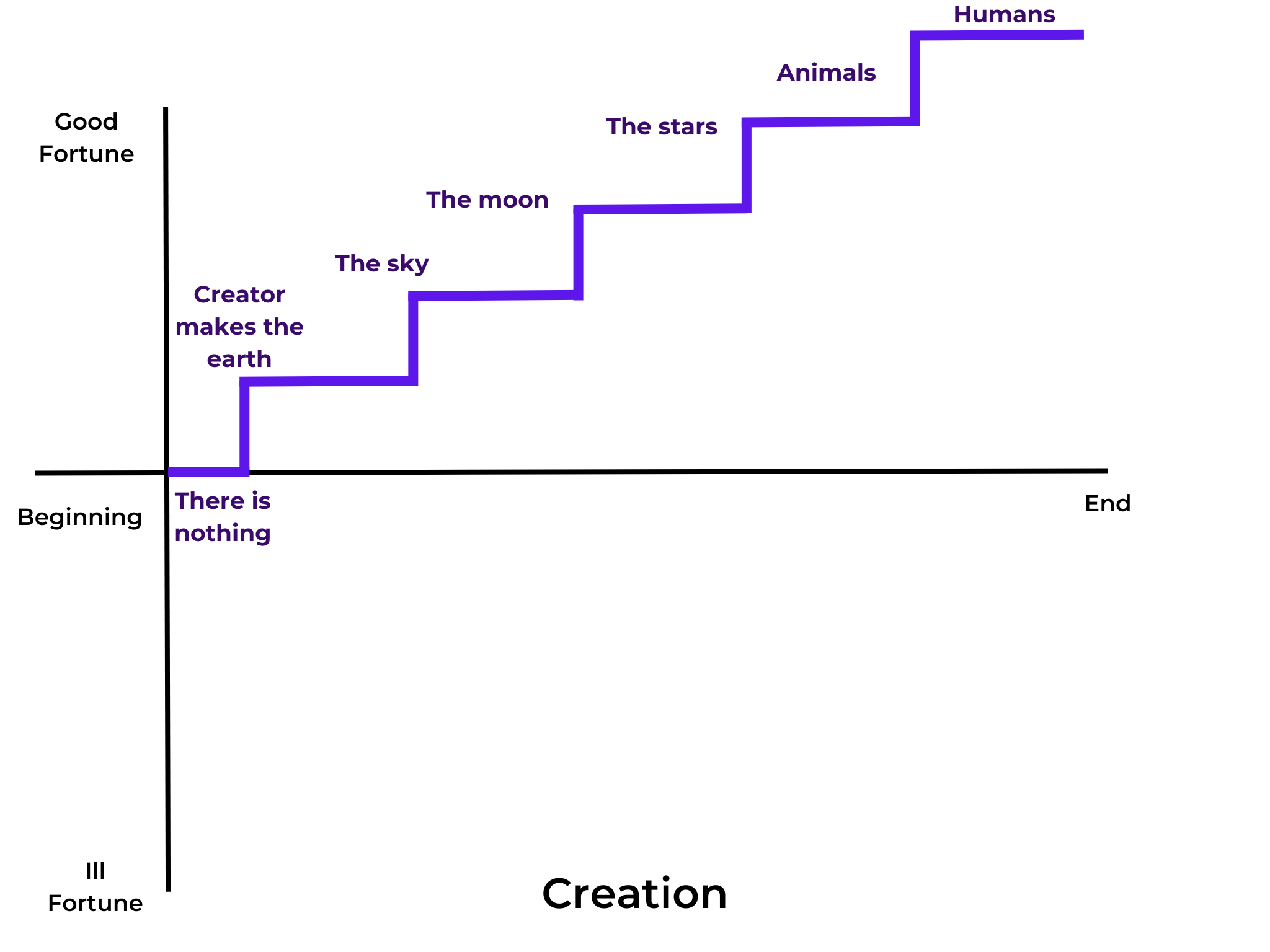

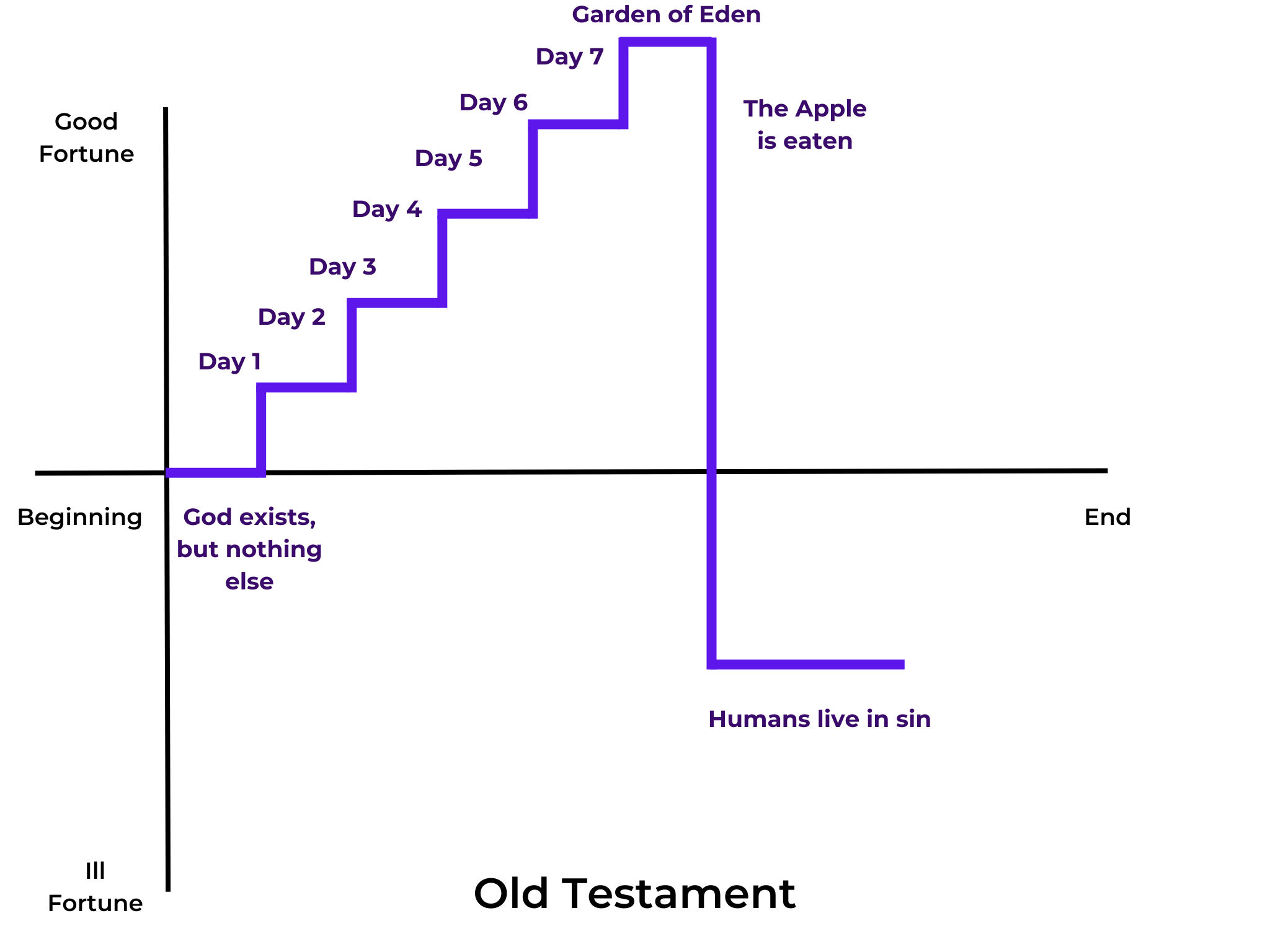

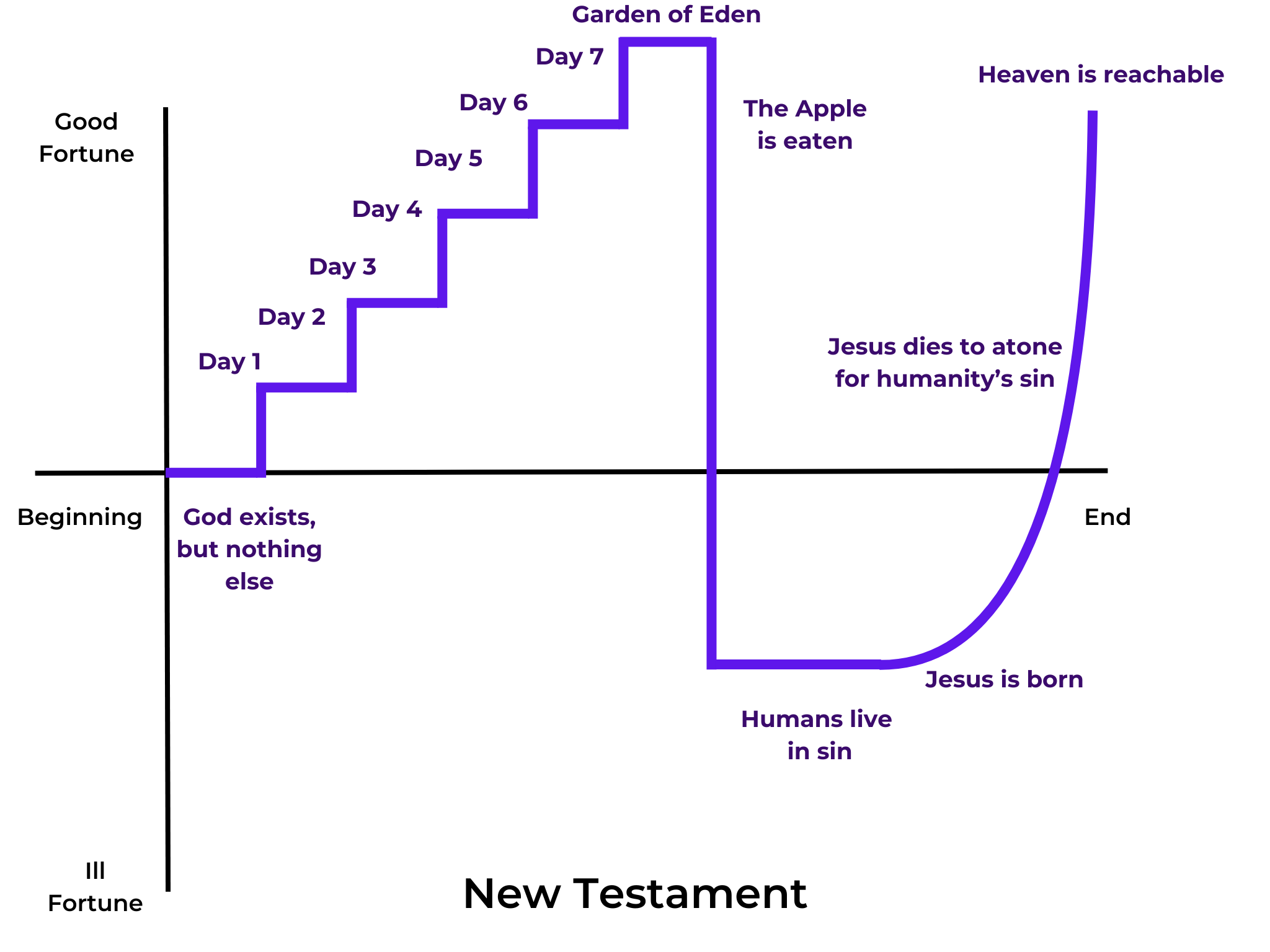

Vonnegut Story Shapes(talk)

- Failed thesis proposal here at University of Chicago

- 8 shapes Vonnegut thought covered most stories

- Person in Hole

- Person Meets Person

- Cinderella

- Bad to Worse

- Which way is up

- Creation

- Old Testament

- New Testament

-

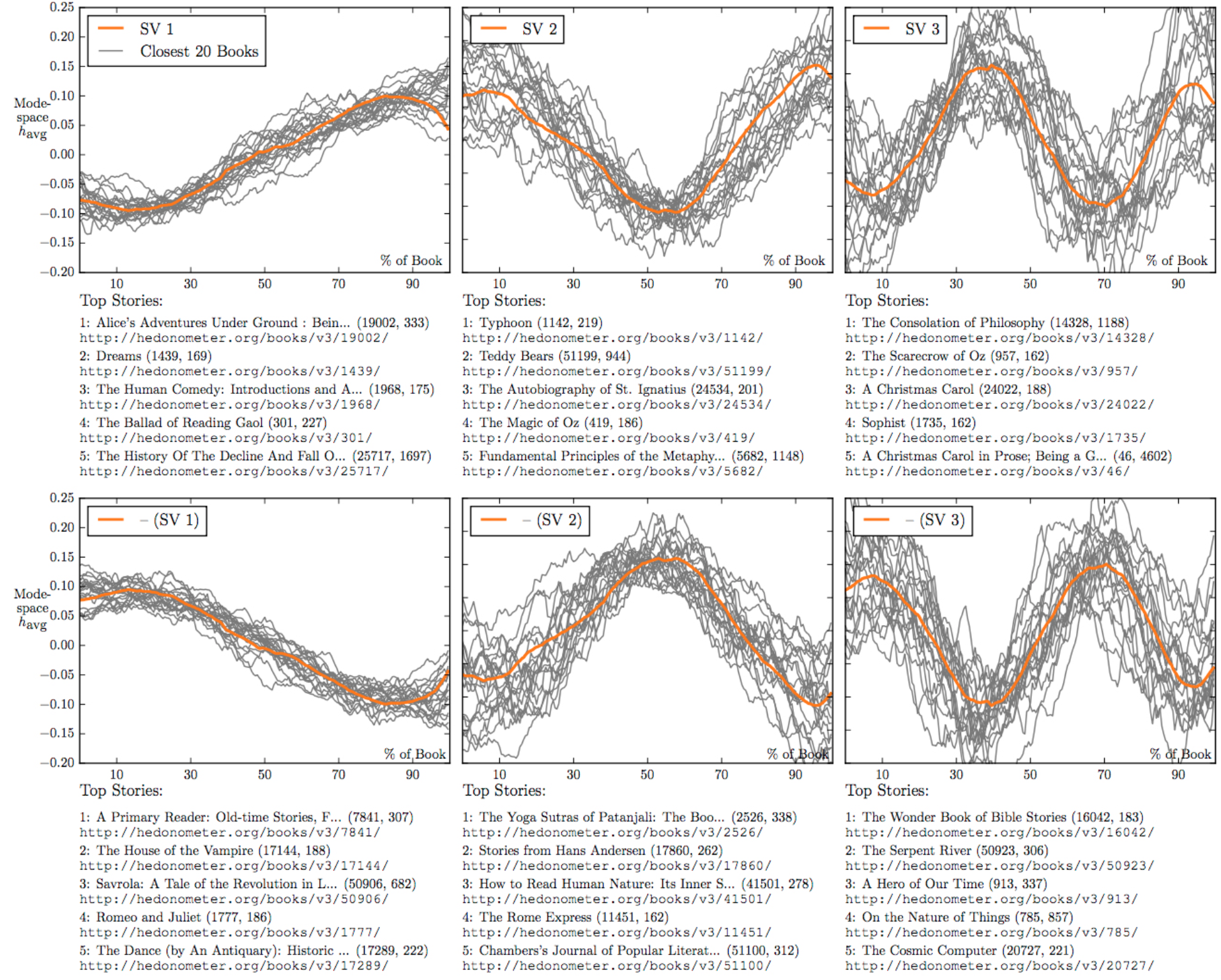

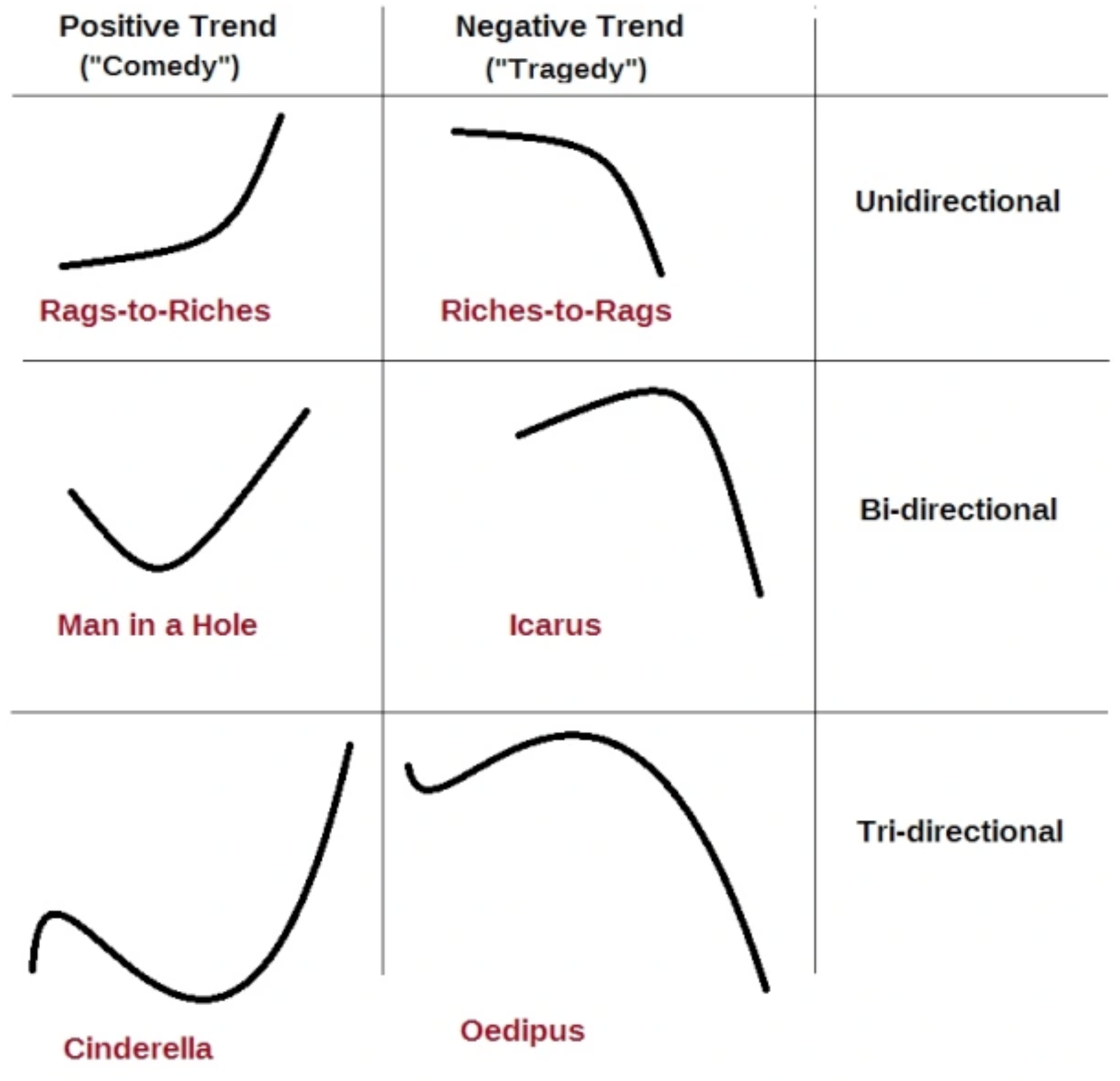

6 Story Arcs Research (Reagan et, al.)

- Using sentiment analysis they found 6 main story shapes

- Two Trends

- Negative and Positive

- Three curve shapes

- Uni-directional

- Bi-directional

- Tri-Directional

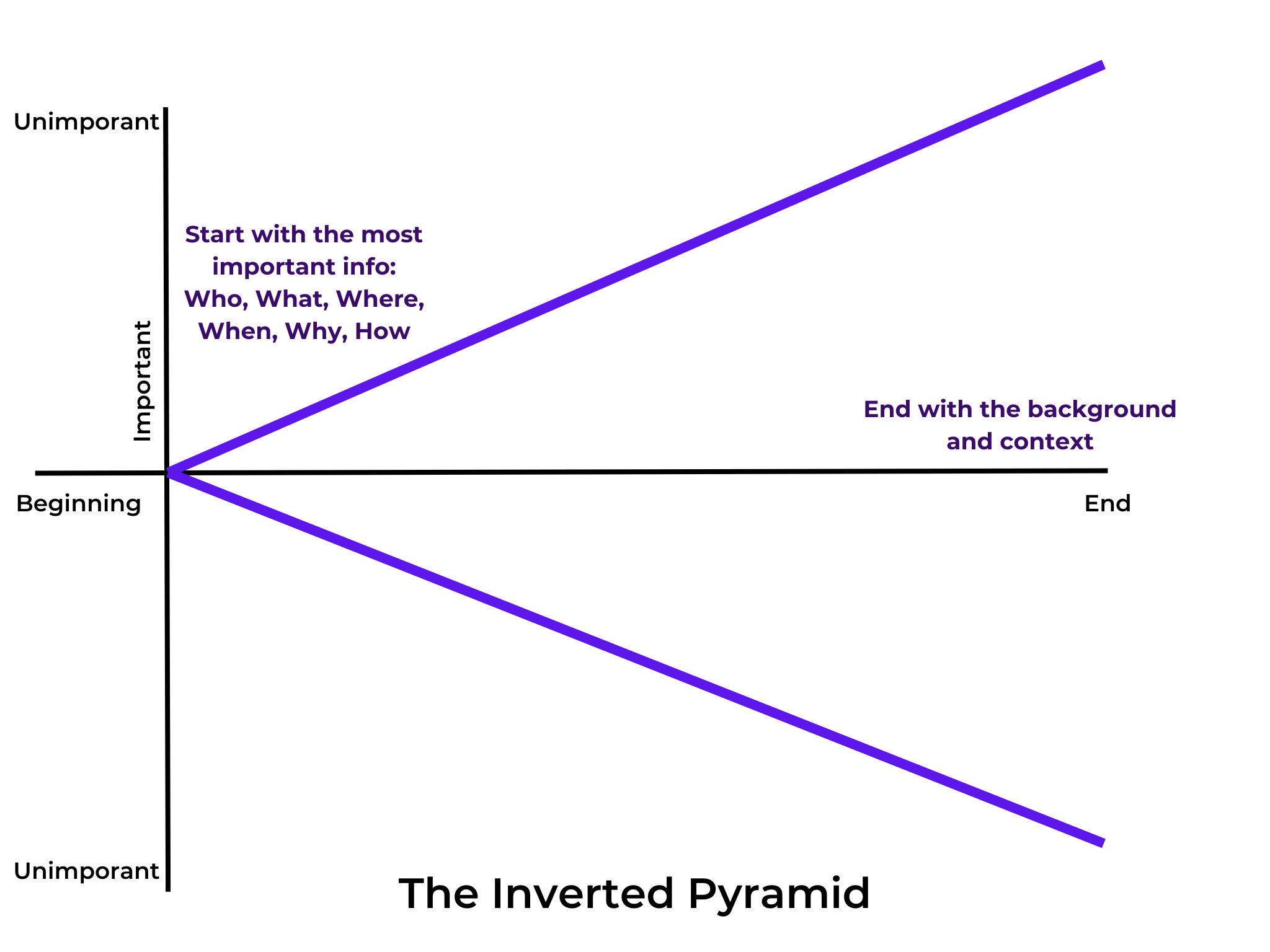

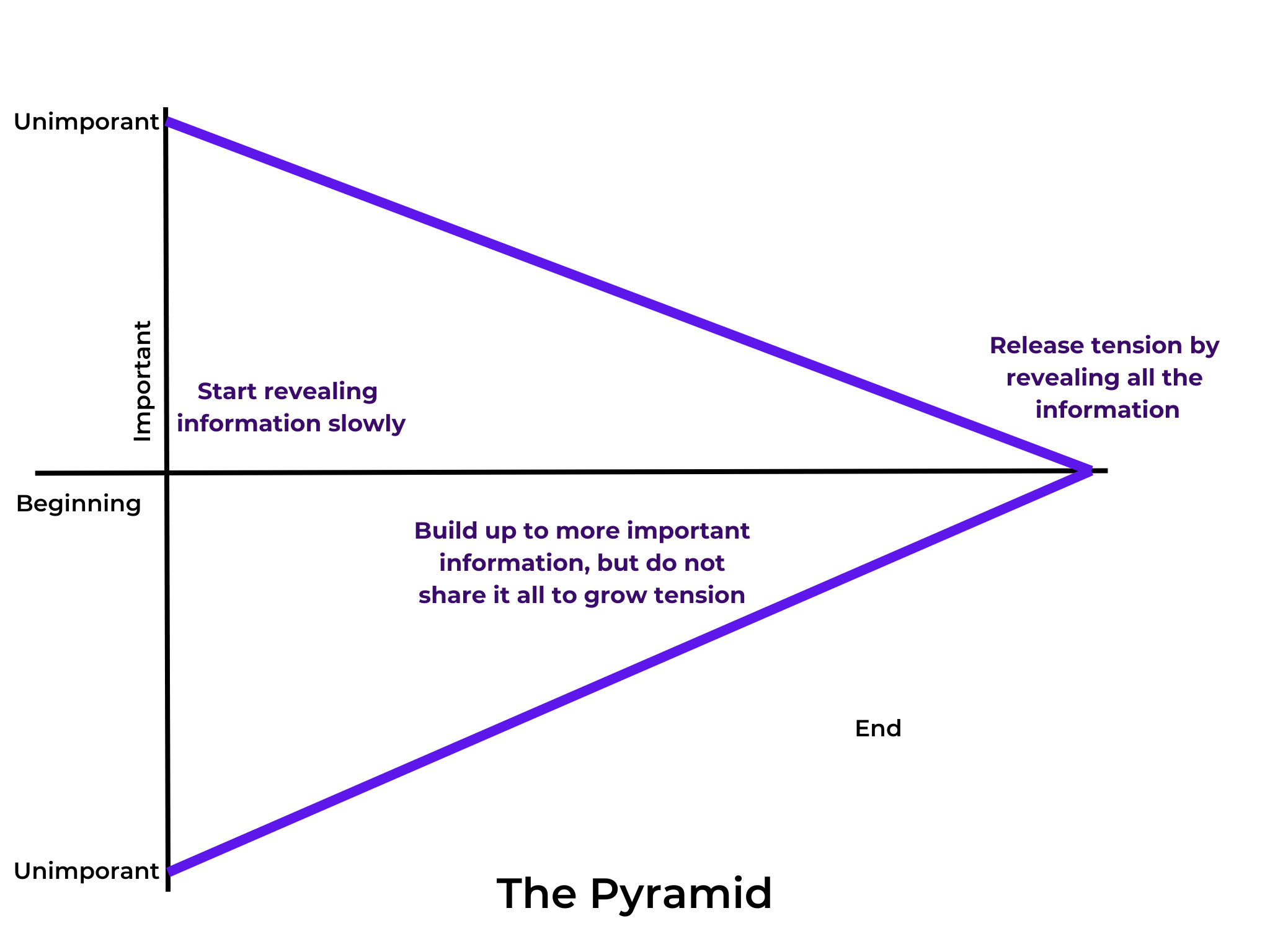

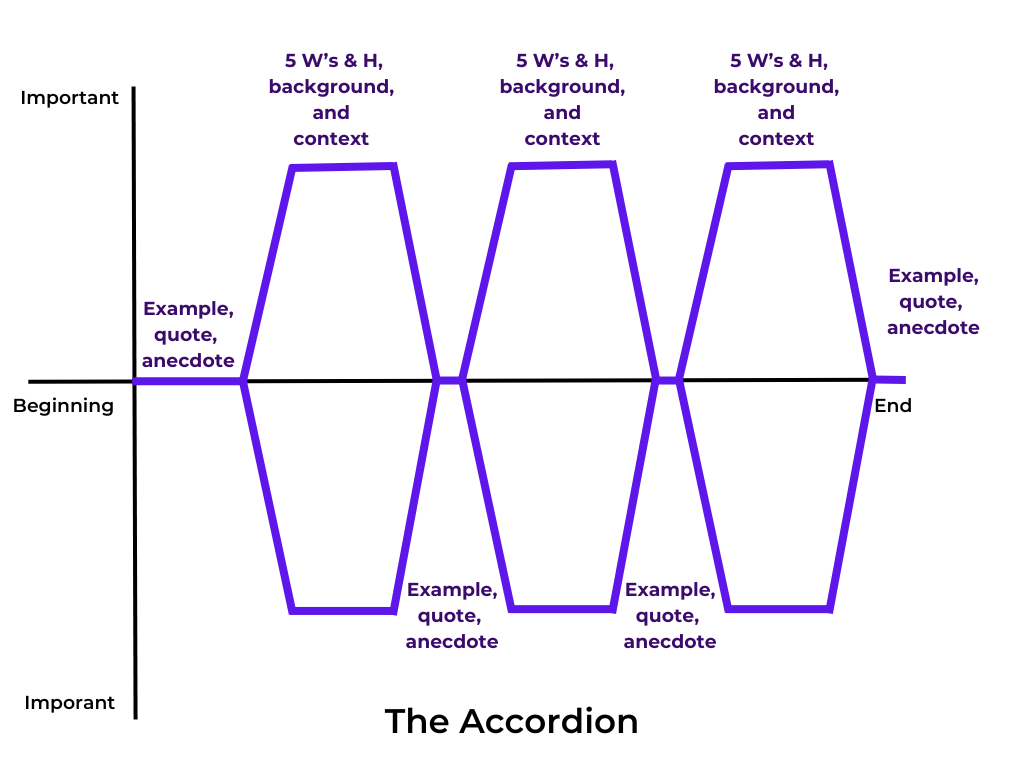

- The Pyramids (Zamith)

- Accordion

- Back to the Future

- Flashes

- Linear

Narrative Jigsaw Activity

- Use your events and change to help identify the structure you used in your outline

- Choose a different one of the narrative structures we just discussed and outline your story again using it as your framework.

- e.g. If your story was originally told from start to finish try starting in the middle or the end and use flashbacks

- Or

- If your story hoped from crisis to crisis to crisis, how about trying to identify the specific moment of climax

- Or

- If your story starts with a lot of background, jump right into the more important information and then provide context after getting your main point across

- This exercise helps people see that their story is not frozen in stone. That its meaning and impact can change if the way it is told is changed. It can also help you see if you are starting your story in the right place. All too often stories are started too early, there is a lot of extra things we want to add because it happened to us and that is natural but the people listening to the story do not need to know our whole lives even if it would be a lot of fun to tell them. We can also often start our stories too late trying to avoid this problem and miss out on the actual instigating moment. Recasting your story through these different structures can help us identify these issues and often find the solution, be it finding a structure that fits the story better or through say a flashback helping you realize what moment you were missing

Putting it All Together

- Not all narratives are stories, but all stories are narratives

- Narratives are just how things are ordered, an anecdote can have a narrative structure but as we know it would not be a story. All stories have some form of structure though

- A Structural Composition

- We can see some of these narrative structures show up within mathematics naturally.

- Research papers follow the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action of Freytag’s pyramid rather closely.

- A person’s research is just a story of struggle with multiple points of change, or any other words it is a Fichtean curve.

- Look at the Hero’s Journey and you may just see the Ph.D. journey.

- But there are plenty of other stories within math where you may want to use a different structure than the one that comes naturally

- Maybe you want to tell the amazing history of prime numbers but you are worried that you won’t be able to hook the audience and so you decide to start with cryptography and then flash back in time.

- Or perhaps you want to tell the Cinderella story of how Quaternions went from Hamilton’s failure to find a workable three dimensional number system to an equation scrawled on a bridge to how the Apollo mission got to the moon

- Then there are the cases where one structure alone is not enough. Thankfully they can be composed together

- Maybe you want to right a book about Indigenous mathematics and how it has shaped our modern world. The overall shape could be the creation structure, but maybe the Polynesian seafaring chapter could be person in a hole, the Aboriginal Australian astronomy chapter is person meets person, and the Maya story of zero is itself another creation.

- We can see some of these narrative structures show up within mathematics naturally.

- To borrow a phrase from Marx

- From each story according to its structure

- To each story according to its needs

- In other words:

- The structure of the story will greatly define how you tell it

- As will what the story requires in order to be told well

- For stories about people, ask yourself: is the person alive, are there experts on a person you can speak with, are any of their collaborators around?

- For stories about a subject, ask yourself: who were the developers of the subject, are their stories integral to the story of the subject, who are the current active participants?

- For all stories, ask yourself: will I be invisible to this story, will I be narrating this story, who might I be at risk of leaving out of the narrative, am I the right person to be telling this story

-

Set the Hook

- Draw your audience in with tension and/or conflict

- Tension

- Ask a question that needs to be answered

- Answer a question, but don’t tell them how or why

- As we expected A led to B which lead to C but then something unexpected happened

- We have always approached Problem X like this, but what if we tried Y

- Conflict

- Are there differing ideas or approaches?

- Is it a long standing unsolved problem?

- Have you tried and tried and failed and failed in your work?

- Are you finally stepping out of the shadows and putting forth work you led?

- Tension

- This should be able to be explained with little to no technical language, that everyone can understand

- Draw your audience in with tension and/or conflict

-

Write in Active Voice

- Someone did the work, it did not do itself

- Active voice emphasizes responsibility

- It is more readable

- Reduces ambiguity

- Passive voice DOES NOT INCREASE OBJECTIVITY (Sainani et al., 2015)

- It is ok to include yourself in your technical communication

- Active Voice is the preference for editors at both Science and Nature

Taking it all Apart

- First Drafts are Key

- Editing is easier than writing, I promise. The hardest thing to do is to get those first words down on the page.

- Each person has their own technique for approaching that empty page. I really like to borrow from the reading and notes method of Niklas Luhmann’s Zettelkasten and the Homework of Life method of Matthew Dicks

- Does it have to do with THE CHANGE or your POINT?

- When editing the top thought in your mind should be: does this character or this event have to do with the stories CHANGE or with your POINT?

- Because if not then it doesn’t need to be there. Now the relationship to the change or point can be indirect, aka it is an event which causes an event which causes an event which causes the change or information you need to know in order to understand the information you need to know to understand the point, but if there is no line of causation I cut it

- When editing the top thought in your mind should be: does this character or this event have to do with the stories CHANGE or with your POINT?

- Workshopping hurts in the best way

- There is nothing better than getting other people’s feedback on your stories. It can hurt when people do not like your favorite turn of phrase or get confused during the section you spent the longest time on, but I have never had a story get worse because I listened to what someone else thought about it. That doesn’t mean I always take their advice, but at least listen with an open mind. After all the story is rarely for you alone, you want other people to understand and enjoy it

Workshopping Activity

- From one of your outlines tell your story to your partner in 2 minutes or less

- Partner, listen very carefully and provide feedback

- Share three things that your really liked about the story

- Share three things that you might do differently

- This activity helps people get a sense of how other people will hear their story and the things that they will connect with and the things they will not. It is also really good practice receiving feedback that is not all entirely positive

Sam’s Favorite Storytelling Tips

- Embrace the Humanity

- People love stories, we have been a storytelling culture for as long as we have had spoken language and we will continue to have it until we manage to kill ourselves off or the universe dies heat death, whichever comes first. Stories are also absolutely central to being human. When we tell stories we humanize the subjects, be they other people or an abstract academic pursuit like mathematics. By telling mathematical stories we are making mathematics something that is alive and something that humans are a part of. People are able to see themselves within a story and therefore they will be able to see themselves within mathematics

- That said, it is still important that when we tell these stories we need to make sure they are being told by and about the entire breadth of those who engage in mathematics. I want to hear stories about the history of mathematics from high schoolers and about their summer research projects from undergraduates and the story of why the private sector mathematician decided to leave academia and all the funny stories about the famous mathematician who has since passed from their old collaborators. I want to hear stories about what it is like to be a Black mathematician, a woman mathematician, a Latine mathematician, a South Asian mathematician, a queer mathematician, an Indigenous mathematician, an immigrant mathematician, and all of the other possible positionalities and races and ethnicities and origins and intersections that exist out there. I dream of a day when everyone can find a story in which they recognize themselves as well as a storyteller they identify with.

- Passion Comes Through

- When we tell stories we are expressing our passion for the subject as well as our excitement. Those things will help people connect with mathematics.

- Celebrate Failure

- Failure is, other than stories, the most universal human experience. A story of something that went wrong will connect with so many more people than a story of a perfect success.

- Mathematicians, as the ones who do mathematics, are often viewed as a bit separate from the rest of humanity in the same way mathematics is not viewed as being a part of the human sphere. After all if you do not work on something that is human, are you really human? Stories of the way things have gone wrong, where we have failed, are the most illustrative of what makes us human instead of a weird logic robot. And as long as mathematicians are viewed as separate, even stories can not do much to bring people in.

- Leave them with One Good Memory

- Mathematical mime Tim Chartier once spoke with me about his ideas with regard to teaching mathematics for liberal arts students, and he said all he wants is to leave them with one good memory of mathematics. This way the next time someone brings it up they won’t think about how they can’t do math or how they hate it, instead they’ll think about that one cool math trick they learned or that one fun math story they know. This one good memory gives them the foundation to build upon until they not only do not immediately think about how they hate math, they instead are the ones telling the stories themselves.

References

Dahlstrom, M. F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(supplement_4), 13614–13620. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320645111

Dawson, E. (2018). Reimagining publics and (non) participation: Exploring exclusion from science communication through the experiences of low-income, minority ethnic groups. Public Understanding of Science, 27(7), 772–786. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662517750072

Djanegara, N. D. T. (2022, January 27). Why are women of color erased from their own science stories? The Objective. https://objectivejournalism.org/2022/01/why-are-women-of-color-erased-from-the-science-stories-they-helped-create/"

Dicks, M. (2018). _Storyworthy: Engage, teach, persuade, and change your life through the power of storytelling. New World Library. https://matthewdicks.com/storyworthy/

Fiske, S. T., & Dupree, C. (2014). Gaining trust as well as respect in communicating to motivated audiences about science topics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(supplement 4), 13593–13597. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1317505111

Gibson, R., & Zillman, D. (1994). Exaggerated Versus Representative Exemplification in News Reports: Perception of Issues and Personal Consequences. Communication Research, 21(5), 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365094021005003

Glaser, M., Garsoffky, B., & Schwan, S. (2009). Narrative-based learning: Possible benefits and problems. 34(4), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMM.2009.026

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Reagan, A. J., Mitchell, L., Kiley, D., Danforth, C. M., & Dodds, P. S. (2016). The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes. EPJ Data Science, 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-016-0093-1

Sainani, K., Elliott, C., & Harwell, D. (2015). Active vs. Passive Voice in Scientific Writing. ACS Webinars. https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/events/professional-development/Slides/2015-04-09-active-passive.pdf

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1995). Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story. In R. S. Wyer (Ed.), Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story (pp. 1–85). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://web-archive.southampton.ac.uk/cogprints.org/636/index.html

Vonnegut, K. (2009). Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage. Random House Publishing Group.

Zabrucky, K. M., & Moore, D. (1999). Influence of Text Genre on Adults’ Monitoring of Understanding and Recall. Educational Gerontology, 25(8), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/036012799267440

Zamith, R. (2022, August 22). _10.2: Story Structures_. Social Sci LibreTexts.

Post-Credit Tip

REMEMBER TO HAVE FUN WITH IT!